“If you want to master something, teach it”

– Richard Feynman

This winter break, I’ve been going through the English translation of Shilov’s Linear Algebra. The text is a must-read for anyone wanting a fundamental treatment of the subject. I wanted to highlight a proof of a property of determinants that is presented to the point that it’s almost obvious in the book, but has been shown quite poorly on the internet.

First, a review.

——————————————

The determinant is defined as the following expression:

over all such permutations

where:

is the element found at the intersection of the

th row and the

th column

- The sequence

represents a permutation of the first

natural numbers

counts the number of inversions in the given permutation.

Nice. This is a great trophy for the purposes of rigor and, if you were feeling so slow, computation. But, it’s a bit of a pain to unravel to the human brain. So, let’s leave the symbols and enter the world of geometry.

(Excuse the handrawn matrix, LaTeX’ng matrices is annoying as heck)

Let’s unpack the latter two of the three statements I made earlier (ignoring the first for obvious reasons) and provide their geometric interpretations:

2. The sequence represents a permutation of the first

natural numbers”

This statement conveys a way to construct each term of the determinant by satisfying an important definition:

each row and each column contributes exactly one matrix element to that term of the determinant (basically no two elements being multiplied in the determinant should be in the same row or the same column).

We can systematically describe each of these terms by fixing the column numbers and varying the row numbers. Thus we arrive at . But, from the above stated property, all rows must be distinct and we must inclue all rows, thus the sequence of

is just a rearrangement of all possible row values, i.e. a permutation.

Now for the third statement:

3. counts the number of inversions in the given permutation.

Geometrically, an inversion between two elements of a sequence would be shown if an element of a greater column value was to the left of an element of a lesser column value. For example:

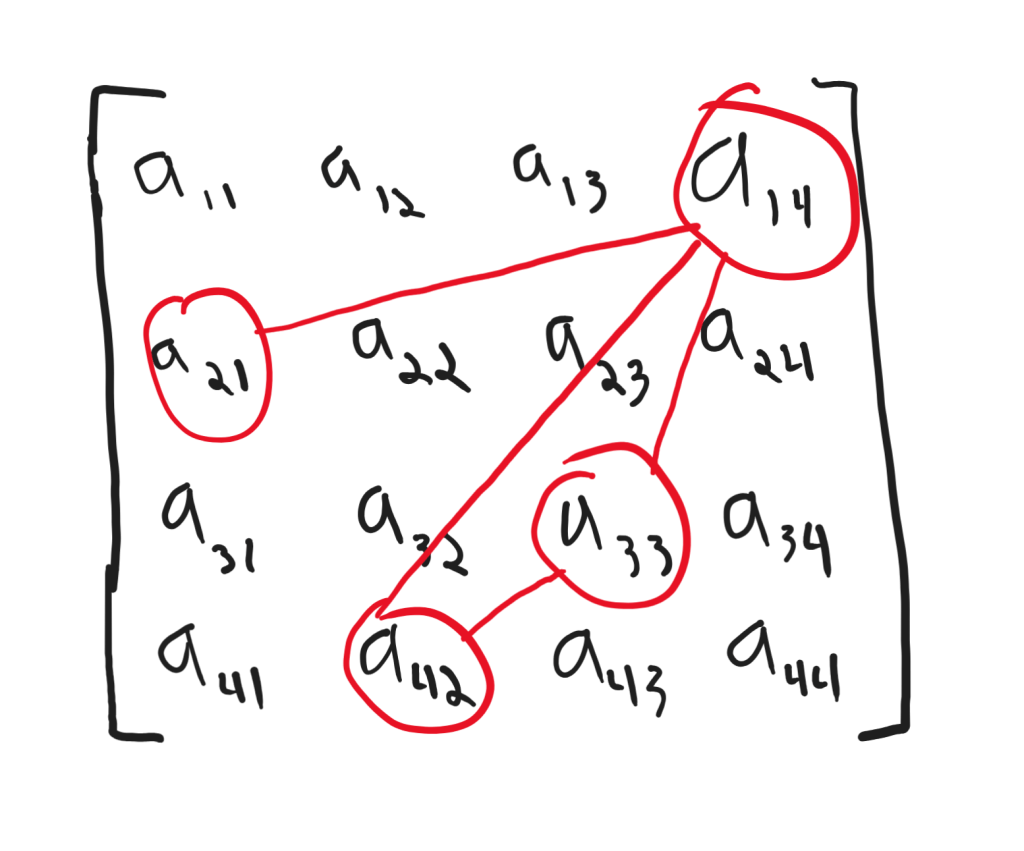

This shows all 4 different inversions between a sequence of matrix elements that satisfy the determinant’s unique row and column policy. Here, the lines connect inverted elements.

But notice the commonality between all these lines; they ALL have “positive” slopes!

This is almost obvious from the definition of inversions, but it allows us to visualize inversions in a much more digestable way than symbols.

So when we want to know the number of inversions in the row sequence of a term of the determinant, all we have to do is count the number of lines with “positive” slope connecting any 2 matrix elements in that term of the determinant (there are, of course, in total)

Now let’s show the following:

“Show that the transpose of a matrix’s determinant has the same value as the original determinant”

To show this we need to show two things for each term in the new determinant.

Firstly, we must show that all elements involved in a term of the new determinant are the same as those involved in the old determinant.

Secondly, we must show that the sign of a term of the new determinant matches the sign in the corresponding term in the old determinant.

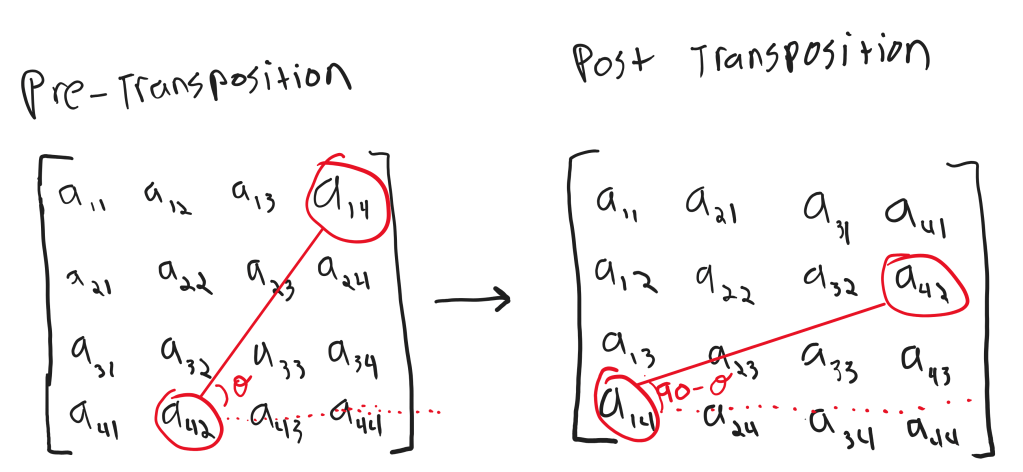

The first statement is clear from the fact that transposition of a matrix can be described as placing the element currently at to

. Thus, the unique row and column property of a term in the determinant is preserved.

To show that the sign won’t change, we invoke our geometric interpretation of an inversion. We can also think of a transposition more geometrically as a rotation about the principle diagonal of the matrix. Thus, a line segment of positive slope would form an angle of

with the rows of the matrix prior to the transposition, and an angle of

after the transposition. In both cases,

remains below 90 degrees so our segment retains its positive slope and thus these two elements remain inverted after transposition.

Pretty cool, eh? Really brings out the linear in linear algebra.

Leave a comment